Bad arguments for RMB appreciation

Imbalances are a poor guide to exchange rate policy

There have been a few op-eds lately calling for RMB appreciation, including one by Setser and Sobel, and another by PAG’s Weijian Shan. These authors maintain that the RMB is undervalued and that an appreciation of the exchange rate would help narrow China’s trade surplus and boost domestic demand via increased consumption spending.

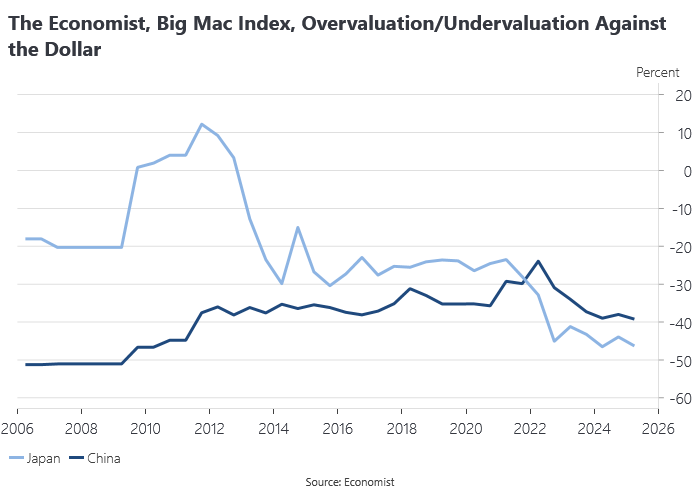

We don’t observe the equilibrium exchange rate directly, so any claim that the exchange rate is undervalued has to be derived from a model of exchange rate determination. The linked authors variously rely on purchasing power parity (of which The Economist’s Big Mac index is a well-known example) and on balance of payments-based equilibrium conditions. Both frameworks have perfectly sound theoretical credentials, but also very weak predictive power except at long horizons that are not very relevant to either markets or policymakers.

As the following chart shows, China’s exchange rate has been managed higher since around the middle of the year, having depreciated in the wake of the Liberation Day tariff shock. But the authors want to see a faster pace of adjustment.

Setser and Sobel maintain that China’s state-owned banks have taken over from the PBoC in accumulating foreign assets, hiding market pressure for appreciation that would otherwise show up as an accumulation in foreign exchange reserves with the central bank.

An obvious question to ask is what China’s exchange rate would do if it were market determined. Even if we put aside the prospect of domestic capital flight, which is what most concerns China’s policymakers, it is hard to make the case for significant market-led exchange rate appreciation. The economy is in the grip of deflation, measured by its GDP deflator. Internal devaluation is more consistent with a managed exchange rate defying market pressure for depreciation rather than appreciation. Many market participants cite China’s low inflation rate as a fundamental basis for its exchange rate to appreciate, but that is arguably getting the causation wrong.

Accommodating deflation

Although it is not commonly referenced, China’s State Council does have a notional inflation objective of around 2%. Calling it an inflation target would be misleading. The PBoC is not running a conventional inflation targeting regime. The 2% objective for 2025 was actually lowered from around 3% in 2024, presumably to narrow the gap with actual inflation outcomes, effectively accommodating deflationary pressure. Suffice to say, domestic inflation is not where the authorities want to see it, as evidenced by the anti-‘involution’ campaign. Even if there is market pressure for appreciation, it is not hard to see why the authorities would want to moderate it.

Setser and Sobel acknowledge this when they say, ‘Chinese domestic prices have been flat or falling since 2023 due to its domestic doldrums while its trading partners experienced modest inflation.’ Domestic doldrums is another way of saying aggregate demand is weak and monetary conditions are too tight. Exchange rate appreciation would only make them tighter, all else being equal. It is reasonable to argue for fiscal or monetary stimulus in this context, but you can make that case on its own rather than as an offset to exchange rate appreciation.

Imbalances

The real reason the various authors want to see an appreciation is their pre-occupation with imbalances. According to Weijian Shan:

China urgently needs to curb its export dependence and pivot towards domestic consumption to ensure sustainable expansion.

Setser and Sobel say:

yuan undervaluation is helping to sustain Chinese GDP growth, but at the expense of aggregate demand in the rest of the world (in particular Europe).

Recall that Setser and Sobel characterise demand as weak, but also maintain that undervaluation is supporting growth, so there is a clear implication that exchange appreciation would make the economy weaker (at least without offsetting stimulus). It should go without saying that other countries with flexible exchange rates have no reason to fear China stealing aggregate demand.

The various authors see exchange rate appreciation as helping China’s economy rebalance away from exports to domestic consumption by making imports cheaper. According to Setser and Sobel:

Though one might argue an appreciating renminbi could unhelpfully add to deflationary pressures, a highly undervalued renminbi incentivises exports and disincentivises domestic demand.

Indeed one might. It is asking far too much of the exchange rate to rebalance China’s domestic economy. The comparison with Japan is instructive. It has a market-determined exchange which is even more undervalued than China’s, at least on the Big Mac index.

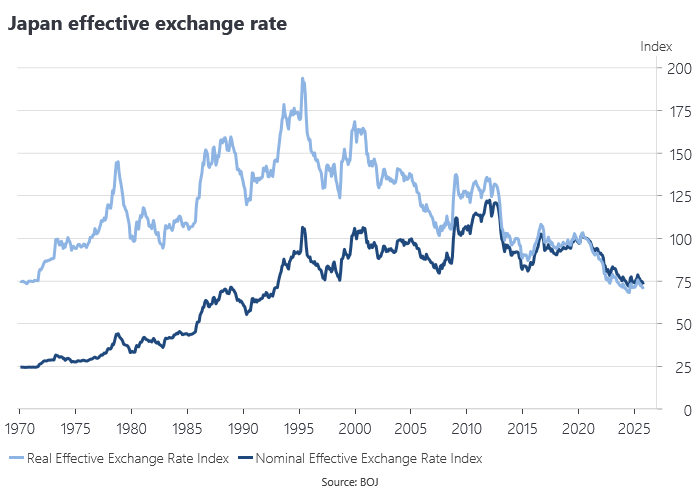

Japan’s real effective exchange rate is around the lowest it has been in half a century.

Yet Japan is running trade deficits, not large surpluses. Obviously there is a lot more going on than just the trade in goods. Exchange rates also reflect the cross-border trade in saving and investment. In Japan’s case, the decline in its real exchange rate is a market-driven response offsetting what would otherwise be declining international competitiveness. Japanese policymakers would no doubt lament the decline in competitiveness, but the weak exchange rate is an efficient, market-led response to Japan’s structural problems.

Obviously, it would be better if Japanese policymakers addressed those problems, as is the case with China. But Japan didn’t address those problems with USD-JPY at around 81 in 1995, or around 75 in the early 2010s. Tight monetary conditions are not going to make policymakers more aggressive about structural reform, quite the opposite in Japan’s case.

It was only with the reflation of the Japanese economy under Abenomics, including a weaker JPY, that the Japanese economy has made some progress, even if it still came up short on structural reform. A weaker yen has been part of the process. Long-duration JGBs have enjoyed higher yields than those on Chinese equivalents since last year and their 10-year bond yields are now more or less at parity. The Japanese economy was once the poster child for secular stagnation, in contrast to China’s secular growth story, but bond yields are implying that China now has the more serious growth problem.

Trade tensions

The advocates for RMB appreciation see a role for China’s exchange rate in ameliorating the trade tensions arising from China’s large trade surpluses. But trade imbalances can persist even in the presence of large adjustments in market-determined exchange rates because they reflect underlying fundamentals, as Japan’s experience suggests. The various authors are only calling for a faster pace of adjustment to what they assume to be undervaluation. Exchange rate changes alone, particularly in a partially closed capital account environment with deep structural distortions, cannot substitute for domestic reforms and fiscal/monetary policy in rebalancing China’s growth model or resolving global trade tensions.

It would be preferable for China’s exchange rate to be more flexible, carrying more of the burden of adjustment to shocks. China’s policymakers should accommodate market pressures for both appreciation and depreciation, but mainly with a view to avoiding domestic rather than external imbalances.

ICYMI

Immigrant Share Grows More Slowly Than Any Decade Since the 1970s.

The Fortune Teller’s Fallacy: A Critical Evaluation of Roubini’s 2026 Economic Outlook.

“During discussions with key stakeholders, the expected distribution of market outcomes across several asset classes for the five potential Federal Reserve chairs was extremely narrow.”