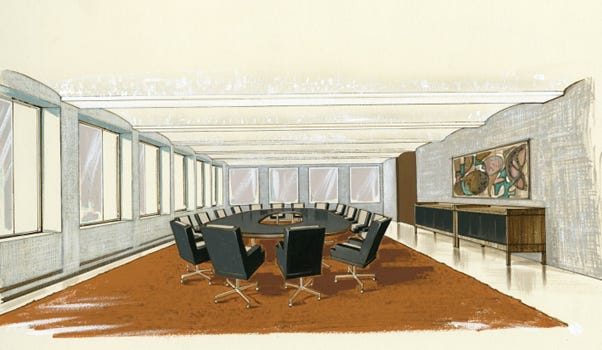

Architectural perspective of the Board Room in the new Reserve Bank of Australia head office building, 1964. Reserve Bank of Australia Archives PA-000271.

There has been some pushback against the RBA Review’s recommendations in relation to the composition of its proposed Monetary Policy Board (MPB). The claim is that the MPB gives too much weight to external, non-executive Board members relative to the RBA executive. It is also claimed that this would make the RBA an outlier relative to the policy committees of other central banks.

The current Board consists of the Governor, the Deputy Governor, the Treasury Secretary in an ex officio capacity and six external, non-executive Board members. The Review does not propose changing that line-up. What changes is a stronger focus on policy expertise on the part of non-executives, moving away from the consensus model of decision-making by making public a non-attributed voting record and giving the Treasury Secretary independence from the Treasurer for the purposes of the MPB.

The claim that this tilts the balance against the RBA can only be sustained if one views the non-executive members under the existing arrangement as more of a rubber stamp. This is exactly the situation the Review is trying to change with its proposed model, but the model does not rely on a change in the numerical balance between executive and non-executive Board members. The non-executive Board members could, in principle at least, roll the two RBA representatives under the existing arrangements.

It is also worth pointing out that once you move away from a consensus model of decision-making, there is no reason in-principle for the Governor and Deputy Governor to vote together. Though rare, such splits have been observed in other central banks, most notably, Lars Svensson’s dissents as Deputy Governor of the Riksbank. His dissent was vindicated by subsequent events, as recounted in this recent profile of Svensson:

Before the financial crisis began, the Riksbank had managed to attract Svensson back from Princeton in 2007 to serve as a deputy governor. By this time, the Swedish central bank was already following Svensson’s advice to publish and justify its interest rate path. And by July 2009, the Riksbank had already cut rates to 0.25 percent.

But Svensson was unable to persuade his colleagues to cut the rate to zero and then to consider negative interest rates if needed. In fact, in 2010 the Riksbank started raising rates. Svensson opposed the move, arguing that the inflation forecast was still far below target and unemployment remained high. He was also opposed to “leaning against the wind.” That was the idea that interest rates should be raised to counter risks to financial stability posed by rising house prices and mortgage debt levels, for instance, even if macro considerations such as inflation and output dictated otherwise.

After a couple of years of polite dissent, Svensson finally left the Riksbank at the end of his term in mid-2013. He forthrightly announced that he had “not managed to get support for a monetary policy” he preferred. Svensson’s former Princeton colleagues rushed to his defense. Krugman called the 2010-2011 rate hikes “possibly the most gratuitous policy error” of the global financial crisis, saying they had “no obvious justification in terms of macro indicators.”

Svensson’s judgment proved right: by 2014 it became clear that the rate hikes weren’t taming housing price inflation and were leading to deflation and economic weakening. The Riksbank was forced to cut rates to zero. And then in 2015 the Riksbank ventured into negative interest rate territory, an experiment deemed successful by a subsequent IMF working paper by Rima Turk.

It would also seem unlikely that the external Board members under the Review’s model would vote as a bloc. The more likely dynamic is one in which most decisions have close to unanimous support, with the occasional one or two person dissent. Dissents are more likely to reflect tactical considerations in relation to the timing of decisions rather than more fundamental differences over monetary policy strategy. It is only at major cyclical turning points that you would expect to see decisions that are more finely balanced, which is exactly when you want policy to be more contested. This is what we tend to observe overseas. Under Chair Powell, for example, there have been only 13 dissents out of 459 FOMC votes cast.