China policymakers shooting the bond market messenger

A market monetarist perspective on Chinese monetary policy

Eswar Prasad had a good piece in the FT highlighting the PBoC’s lack of independence and transparency as major impediment to the formulation and implementation of a coherent monetary policy strategy for China’s economy. Unlike other DM and even EM central banks, the PBoC does not make changes to its various policy instruments based on a predictable cycle of policy committee meetings. Policy changes are made on an unscheduled, ad hoc basis and communicated through press release. Monetary policy decisions are made by the State Council, not the PBoC Governor. It is a framework that not only works against a coherent and predictable monetary policy strategy, but also undermines domestic and foreign investor confidence. It is consistent with the broader subordination of economic affairs to the party-state.

One of the reasons the economy is struggling is that China’s policymakers have been reluctant to ease monetary policy, despite overwhelming evidence that policy is too tight. Some economics Substackers have been arguing about the strength of Chinese economy by parsing retail sales versus broader measures of consumption, but this is missing the elephant in the room.

TS Lombard put out a chart showing the relationship between China’s nominal GDP growth and M1 to highlight both the current and prospective weakness in aggregate demand. I have added M2 to the chart below, for which annual growth is still positive, but pointing in the same direction of weaker nominal GDP growth. From a market monetarist perspective, innovations in nominal GDP are a sufficient indicator of the stance of monetary policy and Q3 is not off to a great start based on the growth in monetary aggregates.

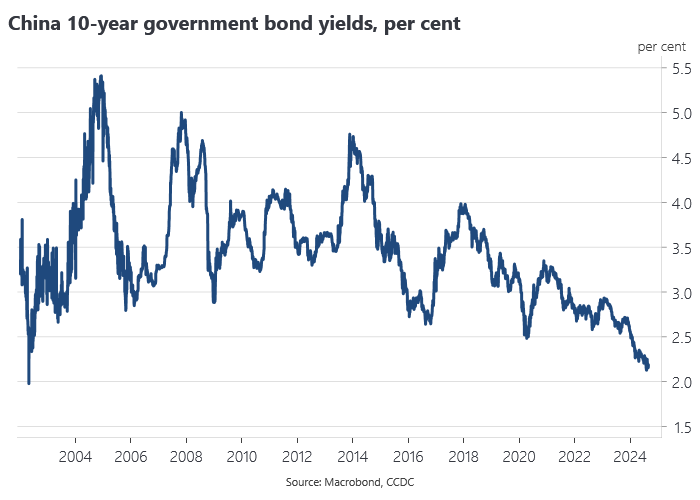

The weakness in aggregate demand is also evident in Chinese government bond yields, which posted lows in yield around 2.13% earlier this month, not far above the record low of 1.98% seen in 2002 amid a global deflation scare that was successfully pre-empted by the Greenspan Fed. China’s 10-year bond yield has been trending lower for a decade.

Bond market intervention and internal devaluation

Rather than taking the signal from the bond market about the need for easier monetary policy, Chinese policymakers view it as an incipient ‘bubble’ requiring corrective intervention. They see speculation as the main driver of lower yields and consider this a threat to the stability of the financial system, explicitly invoking the precedent of Silicon Valley Bank in the US. The authorities also remain focused on deleveraging the property sector and the financial system. The pre-occupation with financial markets as a source of potential instability is consistent with President Xi’s worldview, which sees the development of the financial system as a distraction from the policy focus on the ‘real’ industrial and technology sectors.

It is not yet clear what form bond market intervention will take, although a form of yield curve control aimed at putting a floor under bond yields (rather than a ceiling like the BoJ or RBA) has been mooted by market analysts. The PBoC has been buying longer duration bonds from primary dealers on the same day they were issued by the Ministry of Finance, effectively taking them out of circulation, but with an implied threat they could later be sold back into the secondary market as part of an intervention strategy. The PBoC has created a section on its website called ‘notices on the purchase and sale of sovereign bonds’ to make the threat more explicit.

PBoC sources have also planted media stories talking up the prospects for central and local government bond issuance, suggesting that increased supply will help put a floor under yields and burn the speculators. But overseas experience, not least in Japan, argues against new government bond supply driven by fiscal deficits as a major determinant of yields. So long as China’s authorities remain preoccupied with telling the bond market it is wrong, it will fail to register the market signal demanding easier policy settings.

The managed exchange rate regime remains the biggest obstacle to easier monetary policy. It is difficult to engineer an easing in monetary conditions via a managed exchange rate without inviting speculation, not least in the form of domestic capital flight. Bruegel’s measures of China’s nominal and real effective exchange rate show very little sign of relaxation since the middle of last year on either or a broad or narrow basis. It is worth noting that this makes a nonsense of Trump’s claims that exchange rate is being manipulated for competitive advantage, which is not to deny that this has happened historically.

China’s authorities view exchange rate volatility as a threat and a vote of no-confidence in the system. But that is only true for managed exchange rate regimes. In absence of external devaluation, China will suffer internal devaluation instead.

The prospective intervention in the bond market is best viewed as an attempt to push back against internal devaluation through financial repression, but that will just lead to deflationary pressures popping up elsewhere. Not coincidentally, China’s equity fund managers are under regulatory attack, scapegoated for poor equity market performance as part of Xi’s ‘common prosperity’ campaign.

The very subdued price growth in the domestic economy, in contrast to the rest of the world, largely reflects China importing monetary conditions from the US via its managed exchange rate. It is ironic that for all of Xi’s focus on economic self-sufficiency and suspicion of foreign economic influence, China’s economy remains hostage to the US Fed. While a new Fed easing cycle should help ease monetary conditions through the exchange rate channel, US monetary policy will necessarily remain poorly calibrated to the needs of the Chinese economy.

China provides an interesting case study illustrating how the price-theoretic, market-oriented approach of market monetarism generalises and has considerable explanatory power well beyond its original use case in relation to the post-financial crisis US economy.

Australia’s Q2 national accounts

Australia’s second quarter national accounts are released next week. The Melbourne Institute’s nowcasting model for real GDP growth remains at 0.2% q/q and 0.9% y/y, which is the same as the RBA’s August Statement on Monetary Policy forecast. The Xero SBI-based nowcasting model points to a nominal GDP print of just 2.9% y/y based on the fitted relationship with small business sales growth.

ICYMI

With over USD 600m in volume, Polymarket’s 2024 general election market is the largest and most liquid market in the world for the US presidential election. You can see its central limit order book here. The CFTC fined Polymarket as an unregistered swap execution facility.

Exposing the neoclassical fallacy: McCloskey on ideas and the great enrichment.

Did the ABS open source US personnel numbers at Pine Gap and Northwest Cape?