China syndrome: Why fiscal stimulus won’t cut it

Plus, RBA reform gets attention from offshore

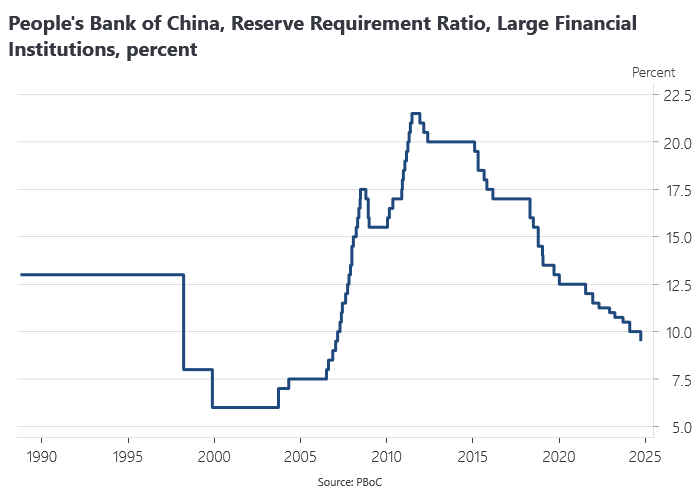

China’s authorities unveiled a raft of stimulus measures this week, including a cut in the seven-day reverse repo rate that serves as China’s main policy rate, as well as a 50 basis point cut to banks’ required reserve ratio. There was an easing in some quantitative lending controls, including for housing. There was also a RMB 500 bn fund for financial firms to buy stock and for companies to engage in share buybacks.

The China share market obviously liked the last of these measures, as did David Tepper apparently, but they amount to little more than a government-funded ‘price keeping operation’ not unlike those the Japanese authorities engaged in during the early to mid-1990s. Moreover, the intervention in the sharemarket is part of a much wider system of financial repression being rolled out across China’s wholesale financial markets.

We have previously discussed the PBoC’s threatened intervention in the secondary government bond market to curb ‘speculation.’ China’s 10-year bond is now only a miserable four basis points above where it was on Monday before the stimulus measures announced on Tuesday. If markets viewed the stimulus package as effectively reflating China’s economy, we would expect this to show up in the long bond rate. Remarkably, China’s ultra long bonds are now trading at yields below those in Japan.

China’s authorities are also engaged in foreign exchange market intervention by proxy, with state banks entering into USD dollar shorts via currency swaps aimed at keeping a floor under the exchange rate. The unwillingness of China’s authorities to allow further significant depreciation in the exchange rate is a large part of the problem. Ironically, the Fed’s new easing cycle will do more for China’s economy via the exchange rate channel than all of the actions of the PBoC.