Commodities for the long-run: are real commodity prices trending?

The Simon-Ehrlich wager 43 years on

This week marks the 43rd anniversary of the Julian Simon-Paul Ehrlich wager on the trend in real commodity prices. If you are not familiar with the wager, I highly recommend The Bet by Paul Sabin, which recounts the wager and its broader social and political context. The wager was not really about commodity prices as such, but rather the broader political, economic and environmental implications of any trend in those prices.

Simon left the choice of commodities and the time frame for the wager to Ehrlich. Ehrlich nominated chromium, copper, nickel, tin and tungsten and a timeframe of ten years, commencing on 29 September 1980. If the real price of these commodities rose, Simon was to pay Ehrlich the amount of the price increase and vice versa. Ten years later, the nominal and real prices of each of the five commodities had fallen, and Ehrlich mailed a cheque to Simon. Simon then proposed another, larger bet, again leaving the choice of commodities and timeframe to Ehrlich. Ehrlich declined the second wager.

There have been other bets inspired by the Simon-Ehrlich wager. In 2005, at the height of ‘peak oil’ alarmism, New York Times journalist John Tierney challenged Houston investment banker Matthew Simmons to a $5000 bet over the future price of oil. Simmons thought that in 2010, the average price of oil in 2005 US dollars (that is, adjusted for consumer price inflation) would be at least $200 per barrel, three times higher than the then price of $65 per barrel. John Tierney was prepared to bet it would be less.

Asked about how the bet was going in 2008, Simmons replied ‘We bet on the average price in 2010. That’s an eternity from now!’ An ‘eternity’ later, in December 2010, Simmons was dead and John Tierney collected $5000 from his estate after the price of oil in 2005 dollars averaged $71 in 2010. While ‘peak oil’ was originally meant to be about the supply of oil, it now looks like it is demand that will peak, not supply.

All bets aside, the trend in real commodity prices is empirically testable, although also a more complicated issue than you might think. The Prebisch–Singer hypothesis literature tackles much the same question. The choice of deflator matters alot and you quickly get into some very profound and complicated issues around measuring long-run price change.

Discerning a long-run trend in real commodity prices is made difficult by the big multi-decade cycles occasioned by demand shocks, such as industrialisation and urbanisation of the Chinese economy in the first decade of this century. The last two years have seen two big short-term shocks in the form of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The pandemic was more a demand than a supply shock, with a massive shift in the pattern of demand from services to goods, quickly followed by a rapid recovery from the pandemic downturn, catching the supply-side of goods market short. The war in Ukraine is a more straightforward supply shock.

Simon’s view was about the long-run secular trend, not about short or longer term cycles, which his view encompassed. Simon fully understood that the long-run secular trend could be interrupted by war and other shocks. Recent gains in real commodity prices by themselves do not invalidate his view. Indeed, in Simon’s view, it is short-run scarcity that drives innovation and long-run price declines.

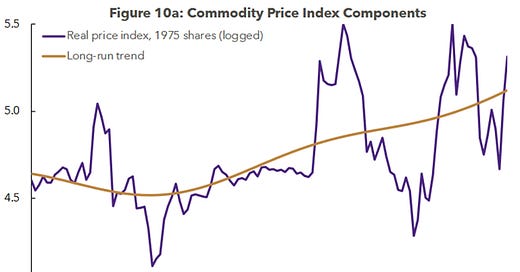

David Jacks’ historical commodity price index has been updated to 2022 and so reflects the influence of the war in Ukraine. Jacks’ index covers 42 commodities, comprising USD 7.43 trillion worth of production in 2019 and spanning the years from 1850 to 2022. Applying value of production weights from 1975, real commodity prices are estimated to have increased by 59.66% (or 0.39% per annum) from 1900, 64.45% (or 0.70% per annum) from 1950, and 32.69% (or 0.62% per annum) from 1975 on his measure. Jacks concludes straightforwardly enough that ‘real commodity prices have been modestly on the rise from 1900.’

Source: Jacks, D.S. (2019), “From Boom to Bust: A Typology of Real Commodity Prices in the Long Run.” Cliometrica 13(2), 202-220, as updated by the author.

From 1980 to 2022, however, real commodity prices have fallen on all of Jacks’ production weighted measures and using equal weights for the 42 commodities. On the latter measure, real commodity prices were 27% lower in 2022 than in 1980. This measure is very much in the spirit of the original Simon-Ehrlich wager. While 1980 was a major peak in commodity prices, which turned out to be very favourable to Simon in the original bet, 2022 was also a major peak. Of the five commodities in the original bet, only tin and tungsten were lower in real terms in 2022 (2019 for tungsten, which is not in the Jacks dataset) than in 1980, although if we step back a year, we could add nickel to the list. This just goes to show that given a flat to slightly positive trend in real prices, a price shock in a given year can flip the original bet fairly easily.

If we were living in a world of increasing scarcity, we would expect real commodity prices to be rising much more strongly than we observe on the Jacks measure since 1900. The literature has still not robustly established a statistically or economically significant long-run trend in commonly referenced commodity price indices and it will always remain something of any open question prospectively. But even a modestly positive trend is still at least somewhat supportive of Simon’s position that in the long-run human ingenuity will trump resource scarcity. The 27% decline seen since 1980 is sufficient vindication of Simon.

Looking forward, there are expectations of big increases in some commodity prices due to the energy transition. De-carbonisation is akin to the industrialisation and urbanisation shocks of the past in this respect, although for the commodity complex as a whole, this is probably more of a relative price shock as demand transitions away from fossil fuels to other commodities. Climate change could also be expected to induce more supply shocks. The Jacks index shows big historical declines in soft commodities that could potentially be unwound by climate change.

However, it is also worth considering that commodity price spikes are a well-known source of political instability, especially in developing countries where low incomes make commodity price shocks especially problematic. The energy transition could also spark a populist revolt in developed economies if handled badly. Some of the price projections for energy transition-related commodities look politically, if not economically, infeasible.

Not surprisingly, Simon was optimist on climate change. In 1995, when climate change was still only an emerging issue, he wrote that:

we now have ever-increasing capacities to reverse these trends, if necessary. And we can do it at costs that are manageable rather than being an insuperable constraint on growth or an ultimate limit upon the increase of productive output or of population (‘Introduction’ in The State of Humanity, ed. Julian Simon (London: Blackwell Publishing, 1995), 18).

Of course, Simon would not have under-estimated the scope for policymakers to bungle the energy transition either.

From a shorter-term perspective, commodity futures have a low correlation with stocks and bonds. Time the cycle right and you can make money from commodities. But even given the multi-decade duration of the energy transition, I would still not consider commodities a good long-run secular bet given an average real return of 0.4% since 1900.

ICYMI

In another blow to the development of prediction markets, the US CFTC rejects Kalshi’s bid to launch retail binary option contracts on US elections. As I discuss in this post, Australia’s securities regulators has banned all binary options contracts for retail investors for 10 years

Anti-ESG funds have outperformed the market since November 2020. As I note in this post, we should expect ESG funds to underperform if ESG investing is to work as intended.

Janan Ganesh predicts US-China detente under Trump: ‘Don’t assume, then, that Trump, if he feels respected on trade, is interested in “containing” China.’

The United States still won't tell us what it wants from WTO reform.