Tariff shocks are aggregate demand shocks

Plus, the 20th anniversary of AUSFTA; and Renee Fry-McKibbin on full employment

The FRBSF released a working paper this week based on 150 years of tariff policy in the US and elsewhere pointing to tariff shocks working through an aggregate demand channel, such that increased tariffs raise unemployment and lower inflation. The paper got a lot of attention, particularly after the Trump administration seized upon the lower inflation result to argue that its tariffs are not inflationary. That is only true if you also accept the transmission mechanism from higher tariffs to lower inflation via higher unemployment and reduced output. In other words, tariff shocks are negative demand shocks.

The results are consistent with my arguments in this newsletter about the Trump tariff shock being disinflationary on net, although I maintain this works mainly through an uncertainty-investment channel, which should also look like a negative aggregate demand shock. The easings in monetary policy seen in the US and other jurisdictions during the course of this year are also consistent with the negative aggregate demand shock view. Some central banks explicitly invoked policy uncertainty when lowering policy rates.

The paper relies on narrative identification and IV estimation. It is not rigorously identified. An important limitation is that there is very little variation in US tariffs for much of the period since the end of the Bretton Woods system of managed exchange rates. Most of the variation took place under conditions of limited exchange rate flexibility. That would force more of the adjustment to tariffs onto the domestic economy.

In the post-Bretton Woods period, we would expect more, if not most, of the adjustment to be worn on the exchange rate. The authors characterise their results as ‘surprising,’ but they are not surprising from the perspective of the policy uncertainty literature. I suspect the policy uncertainty channel is what sits under their results, and the authors also suggest this as an explanation.

In the original Baker, Bloom and Davis paper, the negative effect of a policy uncertainty shock peaks around three quarters after the shock. We would expect the effect of the Liberation Day uncertainty shock to show up in Q4 capex. As it happens, the Trump administration eased tariffs on some food and other imports this week, touting it as cost-of-living relief. But that is tacit admission that the tariffs were inflationary for the goods in question (as distinct from the aggregate price level). Needless to say, the administration can’t have it both ways, arguing that tariffs are not inflationary, but that their removal is disinflationary.

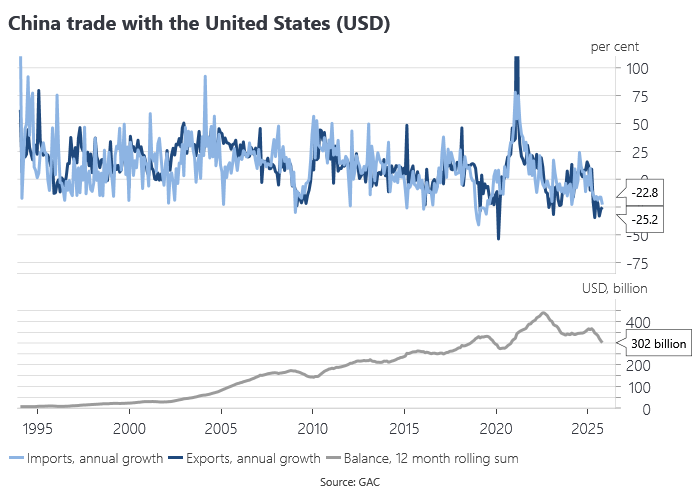

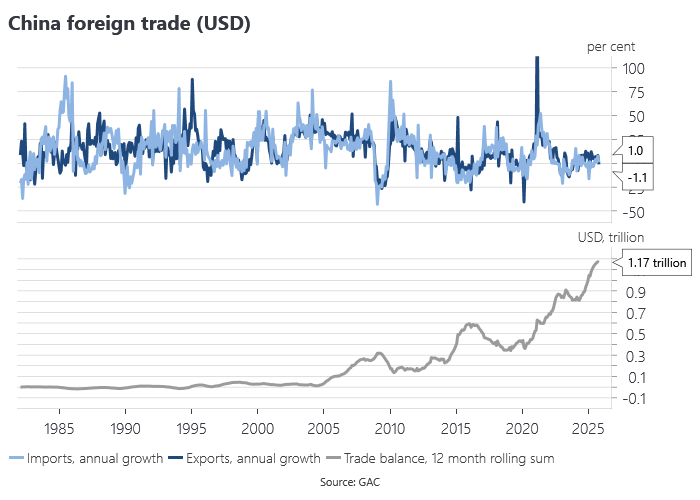

The US data for the year to August had exports to China down 31%, with imports from China down nearly 36%. Fortunately, we have the Chinese party-state to provide the more timely data the US government can’t when it comes to the effects of tariffs on US-China bilateral trade. The Chinese data have exports to the US down 25% and imports from the US down 23% over the year to October in USD terms. China’s exports to the world as a whole only fell 1.1%, pointing to substantial trade diversion.

Trade diversion is still costly and welfare-reducing, even if it mitigates the macroeconomic effects of tariffs. Indeed, Australia’s Productivity Commission used to argue against preferential trade agreements on the basis that they led to inefficient trade diversion, overlooking the potential dynamic efficiency gains from greater certainty in trade policy.