The Federal Reserve Board has released its Statement on Longer-Run Goals of Monetary Policy, the outcome of its five-yearly review of Monetary Policy Strategy, Tools and Communications. This follows closely on the RBA's 10 July Statement on the Conduct of Monetary Policy agreed by the Treasurer and the new RBA Monetary Policy Board.

The two statements are similar in the way they characterise their price stability and full employment objectives, notwithstanding different formulations of their inflation targets. The RBA uses a 2-3 percent flexible inflation target range and aims for the midpoint, while the Fed has a specific 2 percent inflation target. Both acknowledge the dynamic and unmeasurable nature of full employment. The RBA explicitly highlights its communication on balancing objectives, while the Fed describes its objectives as generally complementary but adopts a balanced approach if needed.

Both the Fed and the RBA's frameworks can be characterised as flexible inflation targeting (FIT). The Fed's statement brings to a formal end its experiment with flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT), although FAIT has long since been abandoned in practice. Scott Sumner, who was influential in the adoption of FAIT in 2020, is disappointed by the lack of ambition in the latest iteration. Carl Walsh, an advocate for FIT, was also somewhat disappointed.

The full range of tools

One subtle difference between the two statements is the Fed's unqualified commitment 'to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals, particularly if the federal funds rate is constrained by its effective lower bound.' By contrast, the RBA statement is much more qualified in its commitment to what it calls 'other monetary tools.' There is no mention of a zero lower bound constraint and the statement imposes some additional process obligations on the Monetary Policy Board in relation to their adoption, while also mandating an exit strategy 'at the outset.'

I have argued previously that the 'monetary policy tools' section of the RBA statement should be dropped, although the Fed's strategy statement is perhaps a better alternative model in making explicit that monetary policy should not hide behind constraints on its main policy instrument as an excuse for not meeting its mandate.

The other element of the Fed's statement that is also arguably a good model is its acknowledgement that 'The inflation rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy.' This might seem like a statement of the obvious, but failure to explicitly acknowledge its responsibility for the long-run determination of the price level has historically allowed the RBA to hide behind other factors in its discussion of inflation. Former Governor Phil Lowe would routinely reference a laundry list of non-monetary factors to rationalise low inflation, everything from globalisation to robots. It is important that the MPB acknowledge that they are responsible for the long-run price level. I would extend that to a statement in which the MPB acknowledges its role in the determination of nominal GDP to underscore its ownership of aggregate demand. Nominal GDP targeting follows rather straightforwardly from that acknowledgement.

The forgotten mandate

An under-discussed element of the Fed's statutory mandate is its commitment to 'moderate long-term interest rates,' something that Lars Christensen calls 'The Forgotten Mandate.' That objective could thought to follow naturally from the commitment to price stability and full employment. If there is a long-run relationship between nominal GDP and long-term bond yields, it is also compatible with explicit NGDP targeting.

But as Lars notes, this part of the Fed's mandate could be used to rationalise intervention in the Treasury market to cap long-term yields, not as part of its normal conduct of monetary policy in pursuit of its other statutory objectives, but as part of a regime of financial repression and fiscal dominance of monetary policy. That was pretty much what the US had prior to the 1951 Fed-Treasury accord.

That prospect became all too real this week with Trump's attempted firing of Federal Reserve Board Governor Lisa Cook. Cook has already filed suit, arguing her dismissal is unlawful and named the Board and Chair Powell as defendants to stop them from giving effect to Trump's dismissal. (As it happens, I met Cook when she visited Australia recently and was impressed by her curiosity about monetary policy in Australia. She does not strike me as someone who would roll over easily).

The attempted firing of Cook is widely seen as a test case for whether the President could also fire Jay Powell. Given the legal and constitutional questions at stake, this will likely go to the Supreme Court. As Lev Menand notes in this interview, the attempted firing of Cook is effectively downstream of Trump v. Wilcox, in the course of which the Supreme Court suggested the Fed might be a carve out from its comments striking down the independence of other agencies.

That carve out was reassuring to markets in suggesting that the Fed's independence might ultimately be upheld if a Fed firing came before the Supreme Court. But Lev Menand argues it was effectively an invitation for the Trump administration to test the law. If it comes before the Supreme Court, the Court will likely rule in the administration's favour, given the expansive view it now takes of presidential power, a view that is arguably divorced from US constitutional jurisprudence.

Whatever the outcome of the litigation, the direction of travel is clear enough. Trump is seeking to secure a majority of appointees on the Federal Reserve Board sooner rather than later. A Board majority would also give the administration effective control over the regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents who are also members of the FOMC. Their terms expire simultaneously at the end of February in years ending with a 1 or a 6, in other words, next year.

As Jay Powell demonstrates, just because someone is appointed by Trump doesn't mean they will follow his preferences. But once it is established that the Fed Chair and Governors serve at the pleasure of the president (a position Stephen Miran has argued for), it is hard to see how the Fed and US monetary policy remain independent. The Fed's long-term strategy review won't count for much in that context. Janet Yellen had a great op-ed defending Fed independence and highlighting what is at stake.

This is a classic case of cascading institutional failure, in which the failure of one institution (in this case, a politicised Supreme Court) has knock-on effects to other institutions. Once the cascade starts, it can be difficult to stop. The lack of institutional and individual resistance to Trump is surprising to some, but actually makes perfect sense. The more powerful and wealthy you are, the more you have invested in the current system. That makes any decision to resist incredibly high stakes, and there is an obvious collective action problem in doing so. As Lisa Cook's case illustrates, that burden will often fall on individuals rather than institutions. Many will decide that it is better to give up something than risk losing it all, but that individual logic quickly fails at a collective level.

Do markets care?

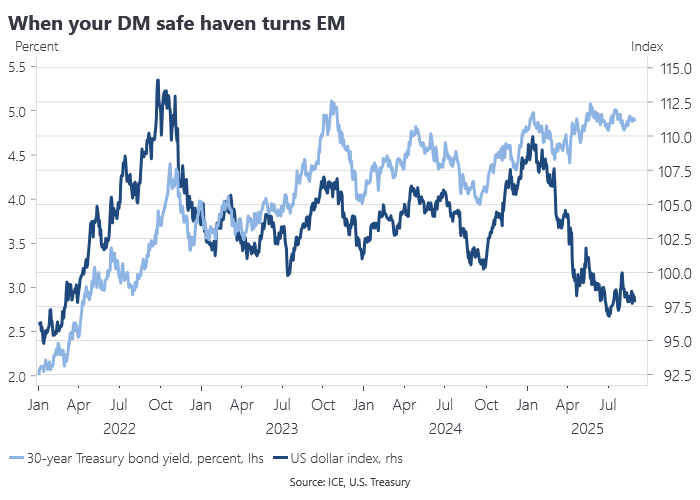

The long end of the US Treasury curve sold off modestly in the wake of Trump's attempted firing of Cook, but markets otherwise showed little reaction. 5y5y forward inflation expectations were largely unmoved, despite the obvious implication of reduced Fed independence for long-run inflation performance.

A Trump takeover of the FOMC is difficult to price, even if we assume the FOMC will follow his policy preferences, which is not a given. Assuming policy is easier than optimal, the short-end of the curve and other assets could be expected to benefit from lower official rates, at least in the short-term, but the long-end of the curve could also be expected to sell off. So shortening duration in the expectation of a steeper yield curve makes sense, but it is very much a 'bear' steepening, and the rise in long-term yields will ultimately challenge valuations in other asset classes.

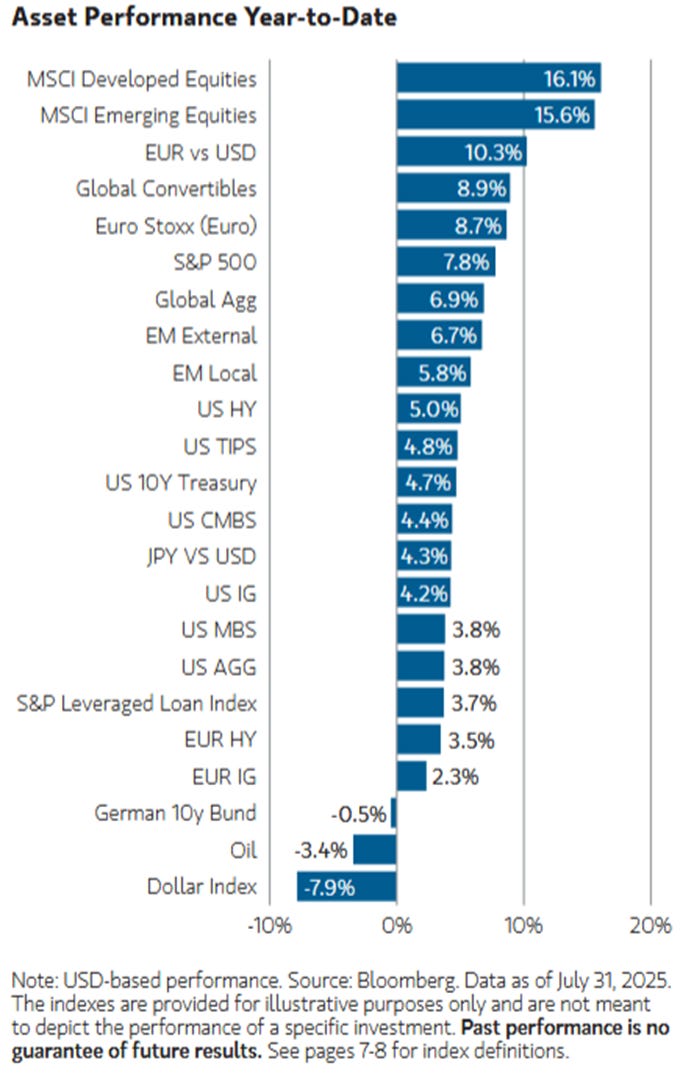

There is one sense in which the US has been sold off, and that is with respect to the US dollar index. As this table from MS shows, the US dollar index is one of the worst-performing asset classes on a YTD basis.

Its weakness is sufficient to wipe out any foreign currency gains on US stocks on an unhedged basis over the same period, which is why fund managers around the world are upping their hedging ratios. The US dollar normally serves to hedge US equity exposures on the part of foreign investors, but as 'liberation day' illustrates, that would be a very dangerous assumption to make going forward. Fixed income exposures are normally fully hedged.

Markets have rationalised a weaker US dollar on the basis that it is historically elevated and mean reversion is to be expected. But that just underscores the downside potential, particularly given that a weaker dollar aligns with Trump's policy preferences. The divergence between long term US Treasury yields and the dollar suggests that US assets have cheapened in foreign currency terms in order to remain attractive to foreign investors. The US dollar is the one element of the pre- and post-election Trump trade that has mostly disappointed and that is probably telling us something.

Damodaran makes a useful distinction between continuous and discontinuous risk in the context of his discussion of country risk premia. His point is that democracies tend to be characterised by continuous risk, whereas authoritarian regimes are prone to the appearance of stability, punctuated by catastrophic episodes of instability. Everything is fine, until it isn't. Markets can price continuous risks pretty effectively. Discontinuous risks, not so much.